Non-GAAP Adjustments: Impact of Merger and Acquisition Activity on Performance Targets and Results

Introduction

One of the more complex issues when measuring performance for incentive plan purposes is how to consider the effect of mergers, acquisitions, dispositions, and the related transaction costs (M&A activity) on financial performance during the performance period. This is due in large part to the difficulty in anticipating/budgeting M&A activity when setting incentive plan targets at the beginning of the performance period and the outsized effect such activity can have on financial results (both positive and negative), depending on the measures being used and the effect the transaction may have on shareholder value. Based on our experience, approaches to adjusting for M&A activity are highly situational, and it is difficult to quantify what constitutes “typical” market practice.

This Viewpoint explores the key considerations that drive the treatment of M&A adjustments, and alternatives companies may consider when determining performance for incentive plan purposes using some common transactional situations.

Key Considerations to Adjust or Not to Adjust?

There are several factors a company may wish to consider when addressing whether and how to treat the impact of M&A activity on incentive plans. These include:

Potential Windfall or Penalty: The inclusion of the acquired company’s financial results may materially affect the expected financial performance used to establish short- and long-term incentive targets.

- A company that uses revenue and/or profitability measures such as operating income, net income, earnings per share (EPS), or earnings before interest, depreciation, and amortization (EBITDA) might easily achieve or exceed its incentive plan targets due to the acquisition.

- A company that uses a capital return metric such as return on invested capital (ROIC) or return on net assets (RONA) might be penalized due to the inclusion of increased invested capital associated with the acquisition.

- A company that divests a significant business unit is likely to fall short of its revenue and earnings targets due to the absence of the divested business unit’s operating results for the full year.

Business Strategy: Acquisition-oriented companies may establish revenue and earnings growth rates that anticipate both organic and inorganic growth when setting incentive plan targets, in which case M&A adjustments may not be necessary/appropriate if the acquisitions fall within certain size parameters.

- A company with a 12% revenue growth rate (e.g., 6% organic and 6% inorganic) establishes a threshold revenue or purchase price level (e.g., $50 million), and any acquisition that falls below the threshold does not result in an adjustment. For acquisitions above the threshold, adjustments are considered on a case-by-case basis.

Tracking/Visibility of Acquired Company Financial Results: In some cases, the acquired company is fully integrated into the financial and operating results of the acquirer, and tracking performance can be difficult. In this situation, it may be easier to add its expected results to the incentive plan’s financial targets rather than trying to exclude actual performance from year-end results. In other situations, the newly acquired business remains a “standalone” entity or is sufficiently large enough where actual results are easily identifiable. Thus, adjusting incentive plan targets or excluding the results from incentive plan calculations are both viable alternatives.

Creating Proper Incentives: Promptly incorporating an acquired company’s expected financial results in incentive plan targets at the time of acquisition helps ensure management has “skin in the game” for the success of the acquired company. On the other hand, some acquisitions may be “fixer-uppers” and excluding their results from incentive plan targets or financial results used to calculate incentives will allow management to make the required operational changes necessary to fairly measure performance. (In the case of companies that use a return on capital or asset measure, the acquisition of a company that lowers overall returns due to high asset/capital and/or low profitability would likely require the lowering of return targets if a decision were made to include the acquired company’s financial results in the incentive plan calculations.)

Shareholder Experience: Some acquisitions may have a near-term adverse effect on the company’s share price, and allowing the financial results to flow through for incentive plan purposes could result in a disconnect between the shareholder experience and management incentive payouts.

- If the acquiring company also uses relative total shareholder return (TSR) as a long-term incentive plan measure, an adverse market reaction to the acquisition could negatively affect the “in-flight” TSR performance cycles. In this case, management may feel unduly penalized for its actions, although some of the TSR cycles may have a chance of rebounding, assuming the acquisition ultimately proves to be successful.

Transaction Timing: Some acquisitions may occur at the end of the year and may have little to no effect on the annual financial results used to calculate incentives of the acquiring company. In this situation, excluding or including the financial results of the acquired company may simply be decided based on convenience. Transactions that close at the beginning of the year could have a more significant impact on incentive plan results, and an adjustment to the reported financial results or incentive plan targets may help to ensure a fair incentive plan outcome. Newly acquired companies can also have a significant impact on open long-term incentive plan cycles; thus, even if the effect of the acquisition is immaterial on the annual and long-term incentive plans ending in the year of acquisition, future results could favorably or adversely affect in-flight long-term incentive awards, and some form of adjustment may be required.

Importantly, M&A related adjustments are likely to attract significant shareholder and proxy advisory firm scrutiny, and additional CD&A disclosure may be appropriate to explain the rationale and impact of these adjustments on incentive plan payouts.

Examples of M&A Activity Adjustments

There are three primary methods for addressing the impact of M&A activity on incentive plan calculations. The first is to adjust the incentive plan targets for the expected impact of the target company post-acquisition, the second is to exclude the acquired company’s results for incentive plan purposes, and the third is to not adjust. In some cases, a combination of all three of these methods may be used based on the facts and circumstances.

Below are some common adjustment scenarios:

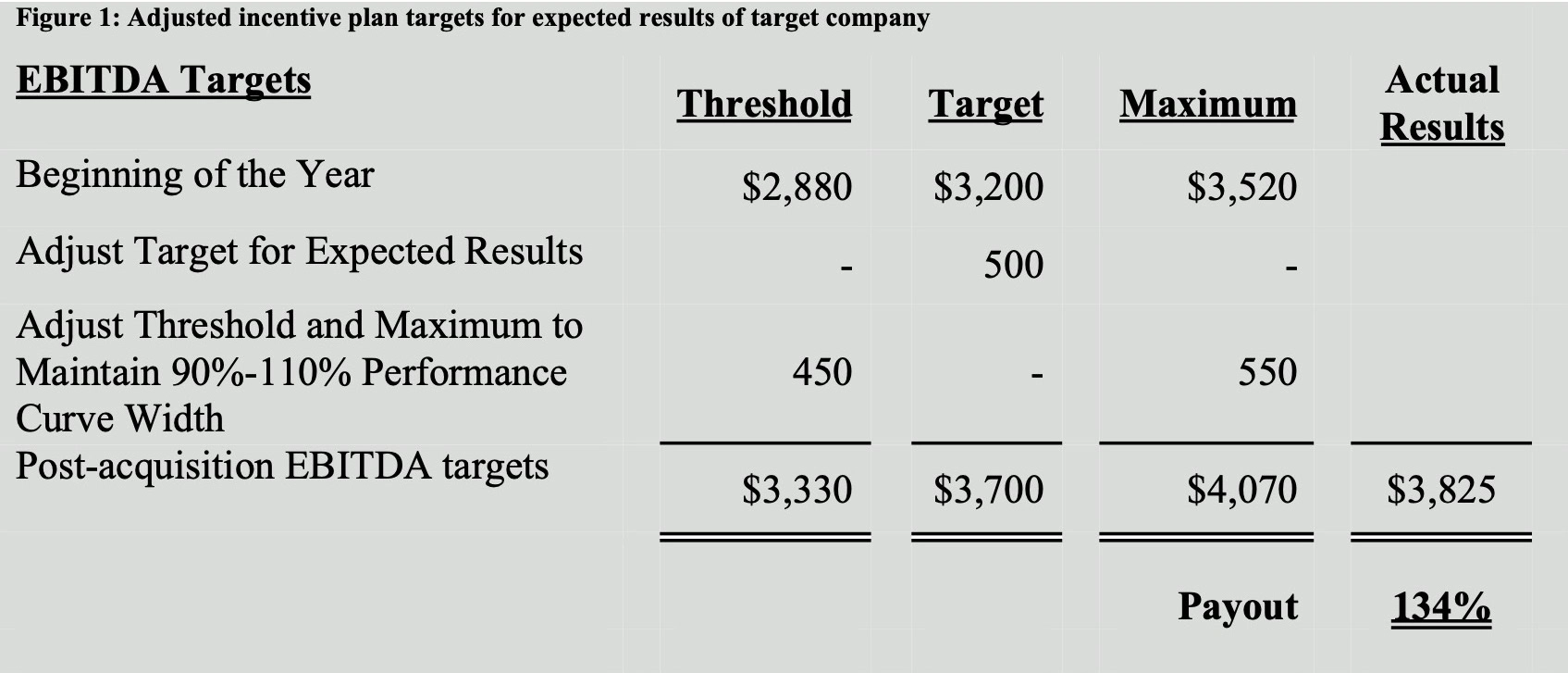

Fully Adjust Financial Targets for M&A Activity: Some companies adjust performance targets for the estimated impact of M&A activity to try to maintain the same degree of difficulty as the original performance targets. These companies will often rely on the business plan/financial forecast submitted to the board as part of the acquisition approval process to increase both the annual and long-term incentive plan targets. However, small, or late year acquisitions may not require adjustments due to immateriality on incentive plan results. Figure 1 below is an example of how a company adjusted the annual incentive plan targets to reflect the expected results of the acquired company. The acquired company outperformed expectations and delivered $565 million in EBITDA (compared to $500 million), resulting in a payout of 134% of target. If the adjustment to the incentive plan targets had not been made, the incentive plan payout would have been at the 200% maximum.

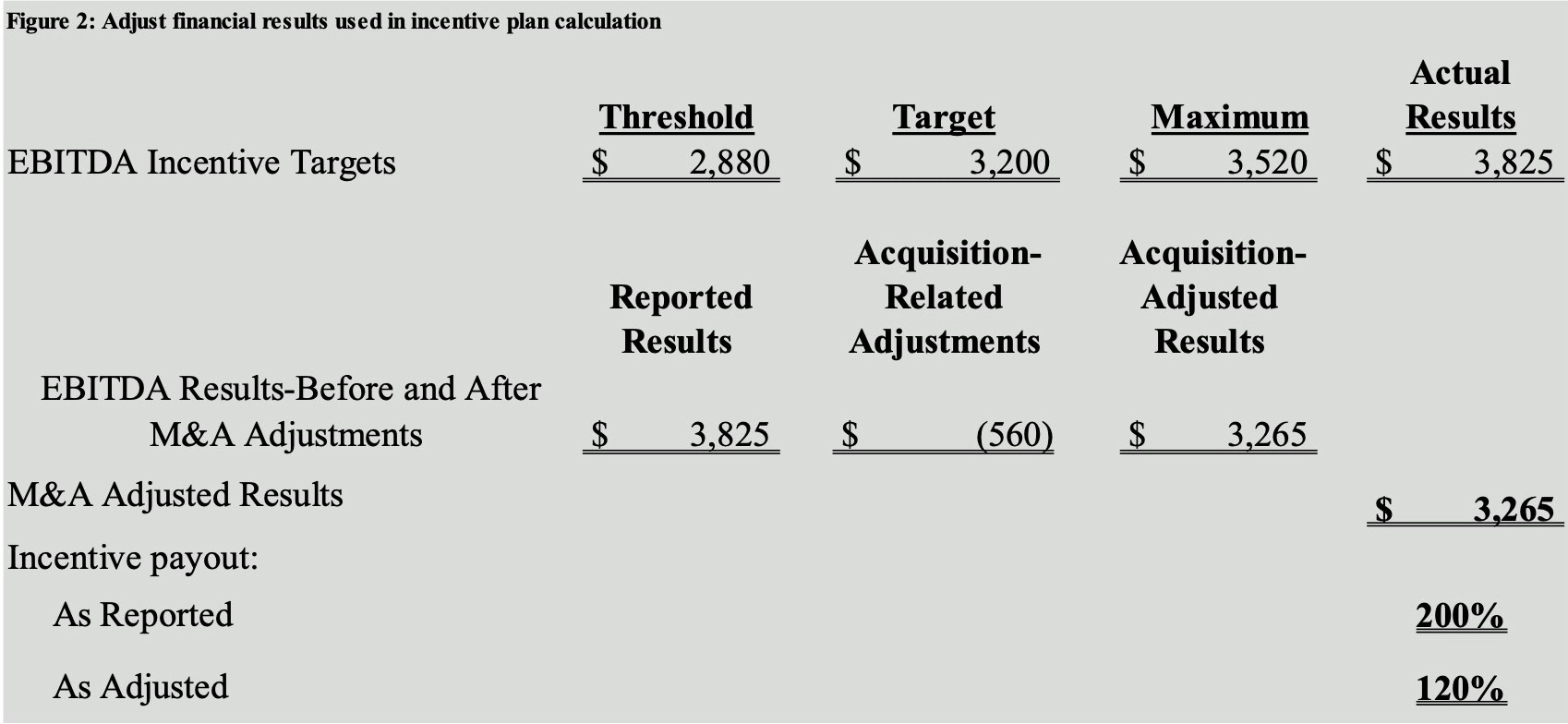

Exclude M&A Activity from Financial Results in Year of Acquisition: Some companies exclude the impact of acquisitions from the financial performance of the company used to calculate incentive plan results in the year of acquisition. Thus, the annual incentive plan and the 3-year performance share plan cycle ending in the year of acquisition are calculated as though the acquisition did not occur. As noted under transaction timing above, it may be necessary to modify the incentive plan targets for the other open 3-year performance cycles. Figure 2 below is similar to the example in Figure 1 except the company excluded the actual results of the acquired company’s EBITDA in the incentive plan calculation, resulting in an incentive plan payout of 120% of target rather than 134%, as the outperformance of the acquired company was excluded from the incentive plan calculation. If the adjustment to the incentive reported financial results had not been made, the incentive plan payout would have been at the 200% maximum.

Partial Adjustment for M&A Activity: Some companies may adjust their financial results for only a portion of the acquired company’s financial performance (e.g., 50%-80%) and allow the remaining portion to flow through the incentive plan calculations in order to recognize management’s success in completing the acquisition. While the effect of the acquisition may have a positive impact on the in-flight incentive programs, the targets for future performance cycles will reflect 100% of the expected performance of the acquired company.

Adjustments Related to Divestitures: Some companies will reduce incentive plan targets for the effect of a divestiture, which allows the company to hold management accountable for the operating performance of the divested business unit while it was under its control. This often works well when the divested business unit is not seasonal or cyclical and is performing well. However, if the divested business unit’s performance is rapidly improving with a strong trajectory for the balance of the year, the company might add the divested business unit’s forecasted performance for the remainder of the year to actual performance when calculating incentives. This approach helps encourage managers to ensure the divested business is operating at peak performance and commands a favorable selling price.

Among the examples discussed above, companies will want to check their long-term incentive plan documents (e.g., grant agreements and equity plan) to ensure adjustments for M&A purposes are permissible. Absent a provision in this regard, any adjustment may result in an award modification for accounting purposes and could result in additional expense and disclosure requirements.

Conclusion

In our previous Viewpoint (Impact of Non-GAAP Earnings and Adjustments on Incentive Plan Payouts: Heightened Scrutiny Ahead?) highlighting the use of non-GAAP adjustments for incentive purposes, we covered the basics of incentive plan performance adjustments, identified the issues important to management and shareholders, and provided some “best practices” for using adjustments and adjusted metrics for incentive plan purposes. We have now highlighted the specific complexities associated with M&A activities and divestitures on incentive arrangements. There are several factors a company should consider when determining whether or not to adjust for M&A activities ranging from the prevention of windfalls or penalties to whether the activities are part of the annual business strategy or are aligned with the shareholders experience. In any event, companies should seek to maintain the performance orientation of their executive incentive plans and promote a fair and reasonable comparison of actual performance relative to performance targets when M&A activities occur during the performance year. Attention should also be given to the appropriate disclosure needed to ensure the rationale behind the treatment is clear to mitigate potential shareholder and proxy advisory firm scrutiny.